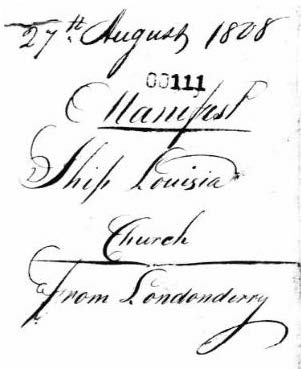

Today marks the 210th anniversary of my family’s departure from Ireland for America—initially for Pennsylvania, then the Ohio frontier. I didn’t know this so exactly until this summer, when I chanced upon the original manifest listing 11 Armstrongs aboard the Brig Louisa, which left Londonderry August 27, 1808 for Philadelphia, at that time the Ellis Island of the Germans and Scots-Irish. We always knew something of the date and even something of the family that came over, but to see their names huddled together in a manifest as passengers in steerage was a moving discovery.

I confess slightly before I found this document, I had already been infected by the peculiar fever of family history. A proximal cause was really my wife’s interest in her own Texas family, which brought me to the Clayton Library for Genealogical Research in Houston. Before I entered, I hadn’t realized it has a wealth of material for the whole United States, and as I walked over to the Ohio section, my eyes immediately landed on volumes for Muskingum County. My ancestors were original settlers in two townships of that county, and there they were in a variety of local records—their lands, their marriages, their graves. That was the edge of the rabbit hole, I’m afraid, and I fell down it completely over the next few months.

There comes a point, I think, where anyone who becomes obsessed with family history and genealogy must wonder why this is happening. It’s not that I wasn’t interested before; I think I was just taking a lot of it for granted, because there were others to do the heavy lifting. My Uncle Don was famously the family genealogist, and we relied on him to get the story straight for many years. And I doubt it’s a coincidence that his passing earlier this year pushed me into feeling greater responsibility for keeping this history alive.

Upon further reflection, I came to realize this obsession was actually a fairly healthy way to process a considerable amount of loss that has occurred over the past five years. In that time, I have lost both parents, two uncles, two cousins and nearly lost a son. So a feeling of responsibility for the family history isn’t just a matter of realizing we are the oldest generation now that our parents are gone; it’s also a matter of clinging to the wider sense of it all. There is a strange if melancholic beauty to reading the wider web of a family’s experience, particularly if it spans so many generations.

What I least expected, however, was to find a role model. My great great great great grandfather Alexander Armstrong came over from Ireland with his brother James and their families, and managed by the end of his life to settle every one of his five children plus his nephew on a farm of their own, with more acreage than they could ever have dreamed of as poor tenant farmers back in northern Ireland. I was inspired by the details I discovered to begin to write up a narrative of their crossing, land purchases, and life on the frontier, which I have titled The Armstrong Chronicles. This will be useful, I hope, for the family; at least I hope it will be mildly indulged. So far I have published Part I and Part II on this site, and will continue the narrative of settlement as time allows in subsequent installments. Part II will at least serve as a guide to anyone interested in seeing the places our ancestors cleared for settlement.

It certainly has been the most constructive way I could find to process the personal losses of the past five years. We live so embedded in our own lives, it is difficult to imagine we are part of a larger story. I now know I can at least draw strength and comfort from that larger narrative web, and I hope others will find so too.

Meanwhile, the series I co-edit with Paul Allen Miller at Ohio State University Press has come out with two new excellent volumes,

Meanwhile, the series I co-edit with Paul Allen Miller at Ohio State University Press has come out with two new excellent volumes,